1965-2025 : 60 ans years ago

- 28 juil.

- 7 min de lecture

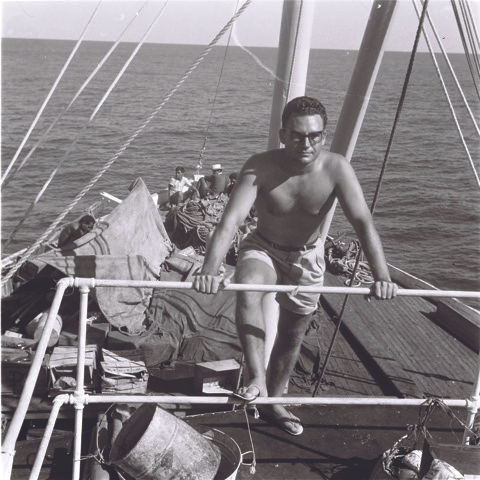

September 1971. In his memoirs, William Reed¹ recalls his first encounter with Polynesian cultured pearls: “I ask Jean Tapu² if it’s possible to see the pearls cultivated by Domard. He sighs, picks up the phone, and gets me permission. I rush over to the Domaines³. All my life, I’ll remember the emotion I felt in that room at the Domaines, when an employee took a small box out of the vault.

The black pearls… Have you ever seen a black pearl? ‘Black’ is a catch-all term. In reality, the pearls reveal an infinite palette of colors, ranging from the deepest ebony to the palest gray, with iridescent overtones—sometimes bronze, sometimes pink, blue, or green. The same goes for shape and size : perfectly round or oval, teardrop- or pear-shaped, flat or full—always soft to the touch and radiant in the light.

© Texte : Patrick Seurot - Photos : archives. Voir copyrights

A feast for the eyes. A sensual delight for the fingers…

I stare at them for a long time, letting them roll across the palm of my hand. Sublime!” “The Pearls of Bora Bora”

The pearls that Bill Reed had the chance to admire came from the 1962–63 harvests in Hikueru and the 1963–64–65 harvests in Bora Bora. It was, in fact, in the exceptional lagoon of Hikueru—where all the ideal conditions seemed to align—that, in 1961, Jean-Marie Domard had Churoku

Muroi graft the first 827 pearl oysters of the species Pinctada margaritifera, variety cumingii, the pearl oyster endemic to Eastern Polynesia. The goal was to produce the first spherical cultured pearls, sixty years after the breakthroughs achieved in Japan.

Following years of exchanges throughout the experimental phase, and while Jean-Marie Domard was preparing an ambitious final stage (see on last page), he wrote on May 1, 1964, to Tokuichi Kuribayashi, president of the Nippon Pearl Company, informing him that “as of March 16, 1964, there remain 1,301 oysters grafted with round cultured pearls in the Bora lagoon.” In this letter, he notified this essential partner that they would be harvested upon his return from France in early 1965.

And it was with undisguised pleasure that he wrote to him again on February 22, 1965, to share his impressions :

“A few days ago, I harvested the pearls from Bora Bora. I found 450. One hundred of them are very beautiful, round, and 11 mm in diameter. Fifty measure 12 mm, five are 13 mm, and one is 14 mm. But what matters most is the color of these pearls. I can’t describe them all precisely, but everyone here found them stunning—more remarkable even than the ones from Hikueru. I believe it is Mr. Muroi’s work that produced such excellent results. I will now ask the Governor to organize an exhibition of all the pearls, from Hikueru and Bora Bora. By the end of February, they will be presented to the press and local authorities.”

Indeed, on February 25, 1965, La Dépêche de Tahiti reported on the first public presentation of these newly harvested pearls at the Chamber of Commerce in Papeete, before a packed audience. (The newspaper referred to the 1,065 pearls as “the pearls of Bora Bora.”)

What Price for Such Pearls ?

As early as April 1964 (see PoeRava 2024), he sent to Tokuichi Kuribayashi in Japan: a parcel of about 2 kg containing 513 pearls, 461 of which came from Bora Bora and 52 from Hikueru; and another, weighing about 1 kg, with 182 pearls

harvested in Hikueru.

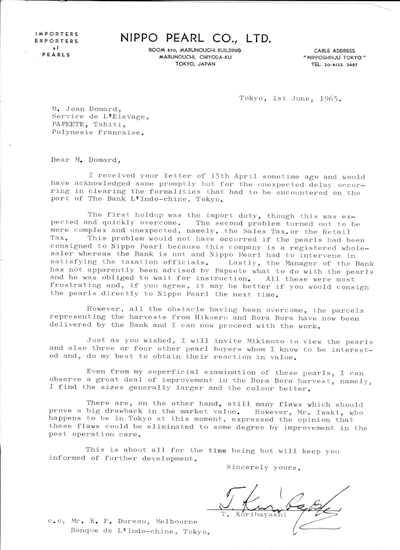

Kuribayashi was informed that he had three months to present them to experts and provide feedback on their quality. He confirmed this in a letter dated June 1, 1965 :

“I observed a remarkable improvement in the Bora Bora harvest, as the pearls appear to be generally larger and more beautiful in color.”

The half-pearls were sent to Japanese experts, who valued them at the same price as those produced in Australia: between 5 and 7 US dollars per unit.

On June 29, 1965, Kuribayashi informed Jean-Marie Domard that Japanese experts were divided over the commercial future of Tahitian pearls. He believed that if an industrial grafting activity were to take place, the maximum would be 10,000 grafts per year, and that only high-quality pearls—perhaps 400 to 500 per year—would be marketable. He suggested that Mikimoto should handle their commercialization.

Most importantly, in his view, to establish their value and prestige, Tahitian pearls should be sold with a certificate signed by the appropriate territorial authorities. This was essential, he argued, because in Japan and elsewhere in Asia, “some people are successfully dyeing yellow pearls to look like black pearls.”

Establishing a Pearl Company

In June 1965, Jean-Marie Domard harvested 110 pearls with small nuclei, grafted in July 1962,

followed by 232 pearls from the last grafting series (small nucleus, January 1963). Kuribayashi did not consider it necessary for him to send them for evaluation.

The years 1965 and 1966 were marked by appraisals of these pearls on various markets and by the formation of a pearl company, along with the drafting of its statutes. The challenges were such that, at one point, the possibility of proceeding without Japanese involvement was considered. Nevertheless, Jean-Marie Domard remained hopeful that a grafter would be able to come between April and July 1966.

Exchanges with Kuribayashi remained cordial and consistently focused on the potential commercialization of Tahitian pearls and their market value. To achieve that, Domard was convinced, a certain volume of pearls was necessary — which meant another round of grafting.

These pearls were beginning to attract international attention: on December 29, 1965, Jean Domard responded to an interested buyer, Jorhen Erikson (from Sollentuna, Sweden), stating that "pearl production in French Polynesia is still at the experimental stage and that the pearls obtained during the trials are not for sale."

Throughout 1966, Kuribayashi continued to emphasize that bringing pearls to market was no easy task and that, in order to secure good prices, only pearls of impeccable quality should be sold. By July 1966, the possibility of selling the experimental pearls was being considered. The lot of pearls was still being shown to potential buyers — in November 1966, for instance, to the Paris-based diamond dealer Perrier.

On Wednesday, August 10, 1966, the draft statutes of the pearl company were approved by the Government Council. The next step was securing approval from the Territorial Assembly.

In December 1966, Jean-Marie Domard submitted a seven-year financial estimate (business plan) for the creation of a study and production company for pearls.

With most of the major obstacles overcome, the signing of an agreement with Kuribayashi’s company appeared imminent — a necessary step before the arrival of a new grafter, Mr. Iwaki, scheduled for early 1967. Meanwhile, Domard identified the next grafting site: Rangiroa, which offered numerous advantages — an airport, a hospital, a weekly flight to Papeete every Thursday, two villages with a ready labor force, and proximity to oyster beds in Takaroa, Manihi, Ahe, and Aratika, all within 20 hours by boat.

The End of the Adventure

But Iwaki fell ill, and on May 12, 1967, Kuribayashi wrote to say he had not fully recovered. He expected to send Mr. Muroi once again and would confirm the date. On June 26, 1967, Domard wrote to Kuribayashi to announce that the Tahiti and Islands Pearl Company (SO.PER.T.I.) had been officially established, with approval from the local parliament granted on June 25, 1967, and that it would likely begin operations around October. In his view, the final investment arrangement would be determined at that point.

On July 19, 1967, Jean-Marie Domard contacted Kuribayashi’s representative in Australia to request a quote for the purchase of baskets needed for farming the future grafted oysters, as well as for an X-ray device to examine pearls without nuclei.

That same month, a conflict reportedly erupted between members of the government and Jean-Marie Domard concerning the handling of an offshore fishing issue, in his capacity as department head — a matter entirely unrelated to Tahitian pearls. Domard apparently sought to defend the interests of Tahitian fishers, while the Governor wanted to transfer management to private companies. In any case, he was summarily dismissed on August 7 and ordered to leave the Territory by August 19, 1967.

1. William Reed: Pearl farmer of Australian origin

2. Jean Tapu: Pa’umotu, diver and former world champion in freediving

3. Domaines: Former territorial agency in charge of public property and assets

What became of Jean-Marie Domard’s pearls?

In 1964, the Governor requested two pearls from Hikueru as keepsakes from the first cultured pearl harvest (letter dated March 22, 1964).

Of the first 46 pearls harvested, 24 were reportedly stolen. When Jean-Marie Domard left Tahiti, he handed over a full inventory of the pearls dated February 10, 1967, which he entrusted to the Fisheries Department: 1,028 pearls, weighing a total of 1,438.45 grams.

In 1971, William “Bill” Reed admired them in a “small box” then kept at the Domaines (Territorial Estate Office). In 1975, Jean-Claude Brouillet expressed interest in acquiring them. According to reports, Jean Tapu facilitated the transaction. Brouillet is said to have remarked: “They’re worth about as much as Russian bonds from the Old Regime.” In his book The Island of Black Pearls, he wrote: “As I admired them, my budding idea transformed into a certainty.”

Did Brouillet in fact purchase Domard’s pearls from the Territory, as rumor has it? Did he take them on a global journey between 1975 and 1980 to show them to the world’s leading jewelers? And are they still today in the hands of his heirs?

The Final Full-Scale Experiment

In 1965, Jean-Marie Domard hoped to perfect the experiments conducted at Hikueru and Bora Bora by undertaking one final grafting operation—this time involving 10,000 oysters. The directors of Pearls Pty were considering sending three Japanese technicians: two pearl grafting specialists for a one-month mission, and a team leader in charge of post-operative care, who would remain on-site long enough to train a local technician. Mr. Kuribayashi’s approval was required for the plan to proceed. Meanwhile, the Department of Livestock and Fisheries was expected to ensure logistical readiness, with the operation to be overseen by a research company whose shareholder structure still needed to be defined.

On February 12, 1964, Churoku Muroi presented his findings: for successful grafting at Bora Bora—10,000 round pearls and 5,000 mabe (pronounced mah-bay)—20,000 high-quality pearl oysters would need to be sourced from an atoll in the Tuamotus. In April 1964, Jean-Marie Domard wrote to Kuribayashi and Ansault, a representative of the Banque de l’Indochine in Japan, to inform them that he would be ready between June and September 1965.

Whether due to financial concerns or difficulties in reaching an agreement on share distribution between the Territory, the Banque de l’Indochine, and the relevant Japanese companies, this final experiment was delayed. Ultimately, in June 1965, Domard learned—courteously, but with no further prospects—that it would not be possible for the Japanese companies to send one or more grafting specialists to Bora.

All the documents presented here are available on the website